Manufactured Psychosis in Silent Hill

by Shoji Higashikata

Silent Hill is a series of survival horror video games created by Keiichiro Toyama and published by Konami. The original tetralogy -- Silent Hill, Silent Hill 2, Silent Hill 3 and Silent Hill 4: The Room -- were all developed by an internal development team called Team Silent. These four games will serve as the scope of this paper as after Silent Hill 4: The Room’s 2004 release, Team Silent would break up. While possessing remnants of the tetralogy’s identity, the Western developers trusted with the Silent Hill IP would be unable to capture the manufactured psychosis of the originals. This isn’t because Team Silent is a legendary team of visionaries that could do no wrong but simply their ideas were cohesive with one another. The gameplay inspires the sound design which inspires the visuals which then inspires the gameplay. Silent Hill possesses a tight and cohesive set of systems particularly manufactured to incite fear, doubt and a sense of psychosis within its player. However before discussing its systems, the era of horror Silent Hill reigns from should be discussed to demonstrate how it differed from its contemporaries.

The horror landscape of the nineties proved that despite low visual fidelity, there was potential. Titles such as Clock Tower (1995), Resident Evil (1996) and Alone in the Dark (1992) demonstrated a clear desire to break away from campy tropes of older horror media. Ironically, all three of these games place their player character in a mansion that they are trapped inside. Within the halls of their prisons are distinct and terrifying creatures with an intent to harm the protagonist. In the case of Clock Tower, it is a single archetypal slasher character named the ‘Scissorman.’ Though the Resident Evil series is known for its more personable slasher villains (Albert Wesker and Nemesis) the 1996 release would primarily feature bestial creatures like feral dogs and zombies. These enemies would act as persistent hunters that could appear at any time -- installing a sense of dread (James, 2023) within the player. Music arises from the silence when they appear and it becomes a battle for survival. This was the birth of a new sub-genre: survival horror.

The caveat of survival horror is buried within the medium’s title itself: survival. But what is the distinction between horror and survival horror? Isn’t all horror rooted in an animalistic sense of self-preservation? Yes, however, the key distinction is the addition of resource management and an emphasis on player choice -- particularly the fear of making the wrong choice. Not enough medicine. Not enough bullets. Not having a proper exit strategy. Games of the survival horror genre put the burden of surviving onto their player. It isn’t a horror movie that functions more as a rollercoaster -- with choreographed ups and downs -- were the only choice a person has deciding whether they want to finish watching it or not. The active component, the requirement that its player must press forward, is what makes it effective.

It could be dissected from the origin that its genre and medium are ultimately its message (Marshall). “Survival horror game” primes a person’s expectations for what they might expect. “Horror” as a genre is clearly designed with an intent to scare its viewer. “Survival” brings the aforementioned caveats of management and player choice. Finally, “game” means that for it to be enjoyed, it must be played. A person must sit themselves in the driver’s seat and render themselves vulnerable to the game’s systems and ultimately their own ability to “win the game.” But ultimately just because the medium states its purpose, if its components are not tightly designed, it loses its ability to be effective. What makes it all effective is its aura and ability to lure in the player into its perspective.

The first game in the series, Silent Hill, is about a father named Harry Mason who is looking for his daughter after a car crash leaves them separated from one another. The deserted town of Silent Hill has been eclipsed by an out of season snow. After exploring a bloodied alleyway in search for clues, Harry finds the corpse of a skinned dog, flayed and strung up on a chain link fence. Suddenly, Harry is ambushed by otherworldly creatures as the world around him suddenly becomes dark. As he falls unconscious, he’s saved by a cop named Cybil Bennett who gives him his first hint about where his daughter might be. What separates this opening section from the likes of Clock Tower or Alone in the Dark is its mixing of all available mediums. The PS1’s controller haptics will rumble, mimicking Harry’s heartbeat. The quiet and understated ambience of the town will begin to swell as Harry’s footsteps become increasingly less audible. As he furthers in his descent, the overworld becomes more bloodied, rust covered and lacks natural lighting. And it ultimately ends in a sequence where you’re left without a method to defend yourself. As Harry wakes up, Cybil tells Harry about the town and the tools she’s left for him.

This is a masterful scene in which Harry narratively is told how to progress his quest while naturally informing the player about key game mechanics. After some pleasantries, Cybil says she’s left Harry a few things to keep him safe: a pistol, ammunition, a map and a few health vials. However, these items are somewhat scattered around the environment, requiring a player to walk around and pick them up manually. This primes the player to look for these items in the future. Before leaving, Harry investigates a mysterious radio, which seems to play nothing but static white noise. As he investigates the radio, a pterodactyl-like creature named the Air Screamer breaks through the windows of the cafe, trapping Harry inside. Now armed, the player has all the available tools to fight off this enemy. After a swift battle, the player should find that they have no more than four to five rounds of ammunition left. With nothing left to do in the cafe, Harry takes the radio and embarks upon Silent Hill. The ‘tutorial’ thusly ends and the primary game emerges.

The Silent Hill tetralogy has a fairly standard cycle of gameplay. Firstly is narrative, second is exploration and finally a puzzle or thematic battle. However, what Silent Hill does to remedy this predictable cycle is by obscuring random encounters within the environment. Due to hardware limitations of the era, the player will never see very much. However, it allows Team Silent to hide things out of a player’s view. With industrial sounds composed by Akira Yamaoka and hollow sound design, the player is left to ruminate about what they can’t see. This problem is exacerbated when radio static begins to play. The radio is a mechanic that when a monster is in a certain proximity, it will begin to play static. The closer it is, the louder and more distorted the audio will become. However, underneath the static are heavy unrhythmic footsteps, cacophonic cries of the damned and the scraping of metal. These sounds haunt the town of Silent Hill and their source is typically not revealed to the player until they’re within lunging distance. The white noise of the radio becomes in a sense, muzak, ambient music that signals a particular mood (Lanza). Joseph Lanza’s Elevator Music discusses Jean Claude Borally’s Dolannes Melody as a popular musical track because of its pan-pipe -- an instrument with a distinct aura that did not see much use. The radio becomes muzak to the player, a [pavlovian] sound that will elicit some sort of fight or flight response. It may either become an auditory tool to evade danger or an omen to signal what’s to come (Neumann, 2007).

The sound of the radio often clashes with Yamaoka’s industrial compositions which use a wide range of bizarre sounds such as metallic door clanging, winging analog technology (televisions and monitors) and string instruments played with sharp objects. Similar to Borally’s use of the pan-pipe, these unusual “instruments” give the soundtrack a uniquely harsh sound that buries itself into the listener’s head. Furthering a sense of harsh noise, some of the sampled noises are used in creature and environmental audio. The line between music and sound design is often hard to distinguish as they all blend together to create an entrancing sense of psychosis. The player is left to wonder if what they hear is a creature waiting to attack, the environment winging in pain or simply the soundtrack. Examples of these overbearing and overstimulating sounds can be heard in tracks such as All, Until Death and Devil Lyric (Yamaoka, 1999). What differentiates Silent Hill from other horror IPs of the era is its willingness to include music in sections without explicit terror. Clock Tower [famously] has a short soundtrack as only its intro, credits and chase sequences feature background music -- leaving the game feeling dreadfully empty outside of a chase. Silent Hill remedies this issue with ambience that tonally fits the environment. While the music is a general ‘tell’ of an area’s safety, the aforementioned background ambience and radio will often undercut a player’s sense of security at random intervals. Just as sound will interrupt the player’s mental processes, the many monsters of Silent Hill will interrupt their physical processes.

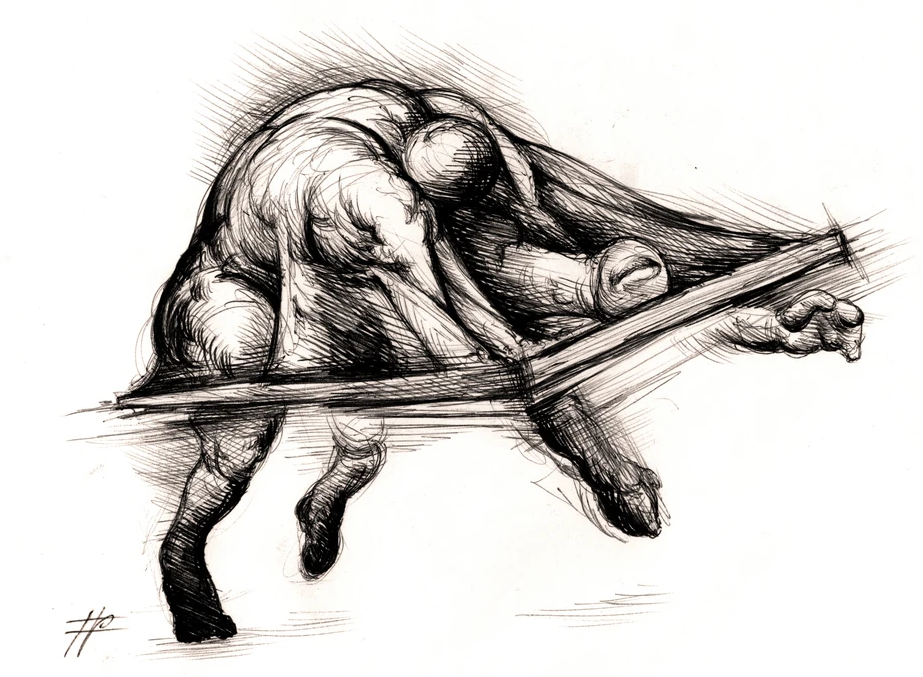

Silent Hill is famous for its surreal and absurdist monster designs. Abstract Daddy and the Closer are two examples of creature designer Masahiro Ito using human anatomy to illustrate a “familiar” yet grossly unrecognizable monster. Abstract Daddy is a monster from Silent Hill 2 is a creature resembling a human laying down on a table. The body of the human and the table meld together to create an analogous, phallic shape of flesh (see Figure 1). The Closer is a humanoid monster from Silent Hill 3 whose “face” is only a single vaginal-like orifice. It stands approximately eight feet tall and drags two tumored arms on the floor due to the sheer mass of them (see Figure 2). They’re not scary purely because of their appearance but because their sheer size will require the player to confront them. Level design in Silent Hill is labyrinthian and claustrophobic by design. The player is often asked to walk down hallways no wider than their shoulders. Because of this, the contextual understanding of the radio shifts for the player as its scope widens from “a monster is nearby” to “they’re blocking your forward path” (Galloway, 2010). A player must listen to their radio, inch closer to see the creature with their flashlight and before they’re overwhelmed, decide whether they should fight or run.

Figures 1 and 2. The Abstract Daddy and Closer, respectively.

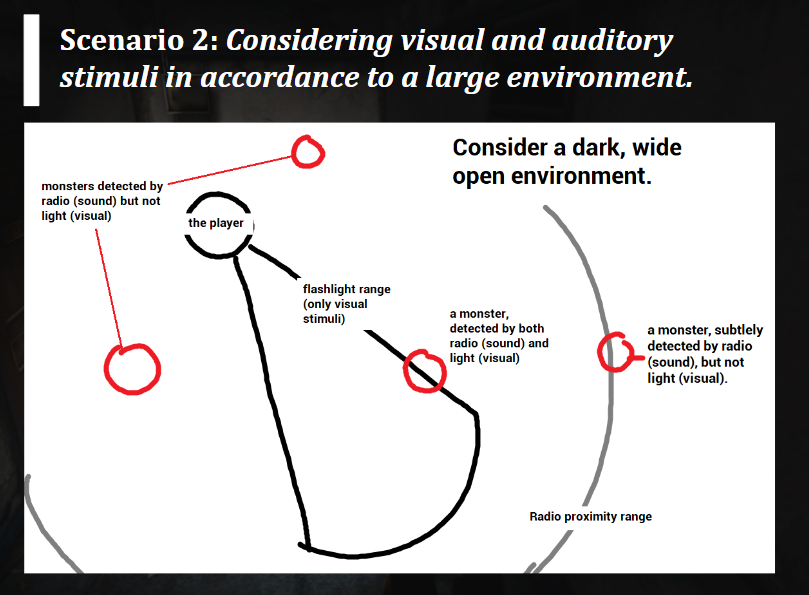

The environment then becomes a creature of its own, inciting subtle messaging that briefs the player for what may come. Wider environments utilize a player’s ability to run away, but due to the low visibility of their flashlight, allow monsters and possible resources to hide in the shadows. Additionally, larger environments means that larger and tougher creatures such as the Closer may lurk in the shadows. Claustrophobic environments typically means that a player will be forced into confrontation at some point in their journey. But because monsters respawn after an unstated amount of time, players must find their way through the environment before their resources eventually run dry. Every encounter becomes more than just a monster, but an amount of bullets to spend and an amount of damage to heal. The manufactured psychosis of

Silent Hill is simply not the horrifying visuals but the doubt it instills within the player. The fear of the monsters soon transforms into a fear of human choice -- that one wrong decision may lead to their own downfall.

The fear of human choice -- or the possibility of making the wrong choice -- then manifests as the player’s ability or right to look. Nicholas Mirzoeff’s concept of the “right to look” stems from colonial America in which plantation slaves -- at the fear of physical violence -- were unable to look at certain things (such as the plantation owner or specifically their wives). This bred a culture in which looking became an act of rebellion that would slowly shift social footing and the power held over oppressed people(s). In the context of

Silent Hill or other survival horror genres, the right to look is an extension of the player’s power. With more healing items and bullets, a player amasses power and thus gains the right to look -- in this case at the monsters that populate the town. This differs from horror movies as the viewer holds an omnipotent role not present in video games because of the medium’s required intractability. While both horror movies and video games are both designed with scaring their audiences in mind, the forced intractability of the video game medium requires its viewer to actively decide whether they possess the right to look or not. This principle will actually physically manifest within the game in the form of the radio and flashlight mechanics.

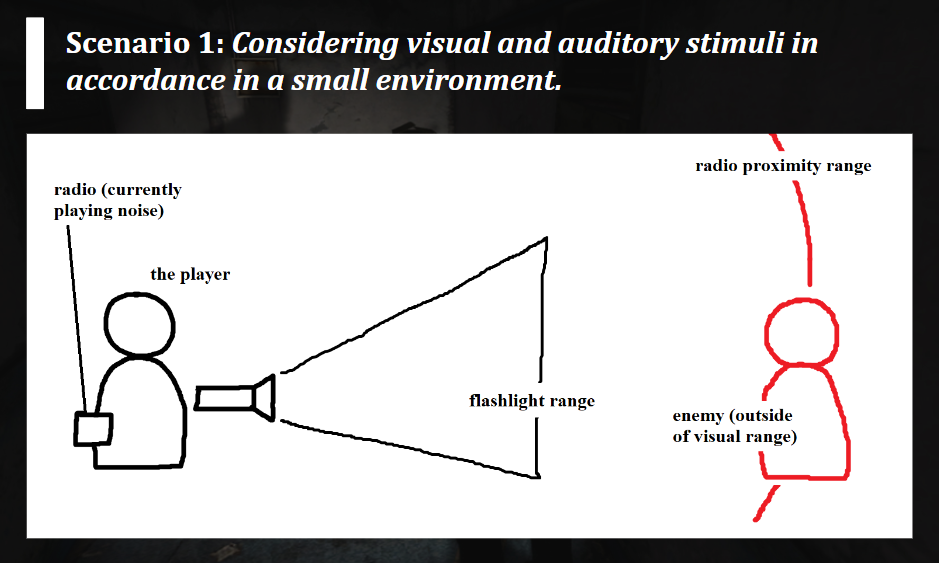

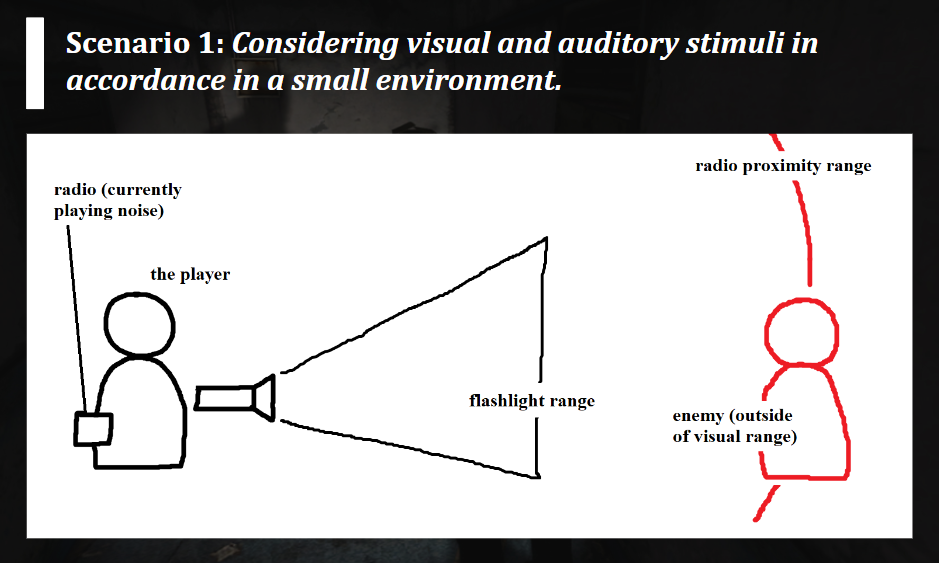

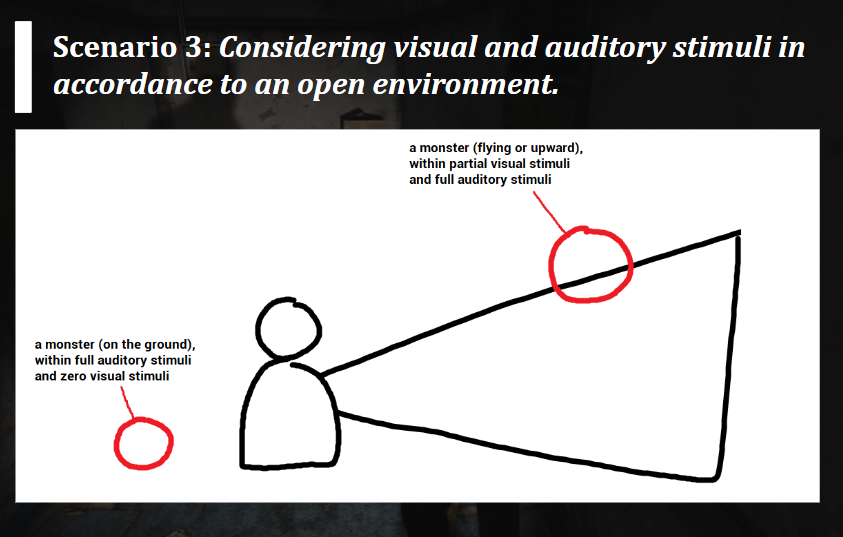

The radio as previously stated is a proximity based audio device that plays white noise and static when an enemy is in its range. The flashlight is a conical light source always attached to the protagonist’s chest which can only light the area in front of the player. The right to look physically manifests as the radio has a larger range than the flashlight. When the player hears an enemy nearby they will always be outside of the player’s visual stimuli (with exceptions). In this moment, a player must decide whether they possess the power to march forward and confront the creature or to turn around, conceding their right to look (see Figure 3).

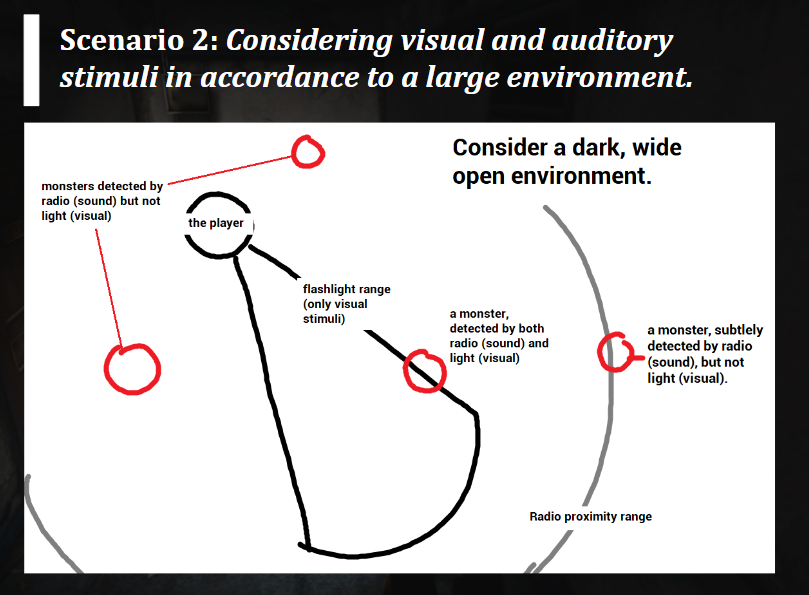

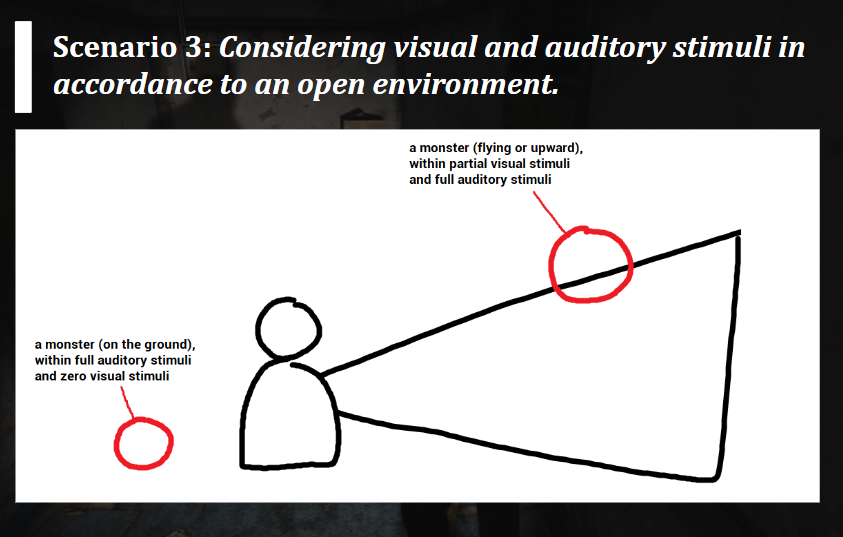

Figure 3. Three visual representation of combat encounters.

Silent Hill’s combat and environmental design defaults its player into a fight or flight scenario. This issue is exacerbated with open environments as the radio does not designate the number of enemies nearby, simply that there is a threat in the area. Paired with the flashlight only able to target a select area, the player is left to scramble around in the dark, desperately looking for nearby threats. Finally, these open world sections are most often where a majority of survival items are scattered. Fear becomes a currency of sorts, where it must be spent in order to ensure player safety. The right to look itself is not a singular action of fighting back, but a continuous system of struggling to maintain power and personal agency.

Silent Hill does feature smaller narratives with non-player characters, however they are often awkward, impersonal or just downright weird. Their introductions are always simple and rarely explain how they ended up in Silent Hill -- but nonetheless they always establish a sense of communitas. Victor Turner’s concept of communitas is the unstructured sense of community built between [liminal] people who submit to ritual elders [during a rite]. The town of Silent Hill -- the ritual elder, in a sense -- creates a rite for its inhabitants through physical and mental battery. Every character struggles through something unique to themselves -- such as

Silent Hill 2’s Eddie Dombrowski and his internal turmoil with his weight and the social backlash he received because of it. Despite their bizarre personalities, their appearances are always a source of humanity and safety. Even with their stilted, late 90s dialogue delivery, their representations are flawed but deeply and instinctively human. The illness and of their appearance comes from the player’s inability to help them. It's never fully outlined to players whether their actions can meaningfully help or affect these people. Items such as Angela’s Knife instill this idea that it has a purpose and

can be used to help aid in her recovery. The player is simply left to dwell on its use, psychotically fidgeting with it in hopes that they make the correct action at the correct time. However, items like this never have an applicable use. While the primary horror/resource management gameplay sections grant player agency, the “human” sections are typically relegated to cutscenes. The player then becomes an observer -- just like within a horror movie -- and thus is unable to save what is the only safe and human part of the town. The juxtaposition of distinctly human characters with the horrors that be create a thick and palpable aura. The town’s aura of psychosis melts in their presence and what soon arises is helplessness. What

Silent Hill uses to sell its horror is its lack of agency with its human characters. With every staggered interaction, the characters slowly begin to lose themselves to the town’s influence and all the player can do is watch as their safe spaces melt away.

James Sunderland, protagonist of

Silent Hill 2, is drawn to the town of Silent Hill after receiving a letter from his dead wife, Mary. Unsure if she could still be alive, he ventures to the town in search of “their special place.” What

Silent Hill 2 changes about the narrative from

Silent Hill 1 is its focus on the liminality of reality. Victor Turner describes liminality as the unstructured state of transition where all members are equal as they all experience a common change in identity (via a rite). Liminality is established both in the literal and theoretical sense. Literal in that Silent Hill is afflicted by the “Otherworld,” a parallel plane of existence that seeps into reality. Through the course of the games, it is often unclear whether the player character is venturing through Silent Hill or Otherworld and the player/character is thus in a constant state of transition. However in

Silent Hill 2 [and beyond], it becomes more theoretical as the rite becomes a meta-physical journey of self-discovery. The Otherworld has an ability to manifest the trauma of a person and allows a character (such as James) to physically overpower it. Once this becomes established, every small little detail becomes subject to analysis. Psychosis then becomes an overpowering feeling of analysis in order to understand the plot.

Silent Hill has a very “show don’t tell” approach to storytelling and requires careful visual analysis to read its subtext. But on the other side, much of

Silent Hill’s surreal imagery is simply for aesthetic horror value. What’s actually relevant evolves into a constant, psychotic internal monologue of symbolic imagery and red herrings.

Manifested by the Otherworld, monsters become extensions of characters and the horror that the player

doesn’t see. The phallic Abstract Daddy becomes an image of sexual abuse and its attacks where it humps like a dog become recontextualized. Similarly, the twitching Closer becomes a manifestation of literal sexual battery. As details slowly reveal themselves to the player, they must reevaluate the actions and visuals that they have previously seen. Does the environment reflect a personal trauma of a character? If so, which character and how does that relate to their relationship with the protagonist? What does this item symbolize? Why is this character acting in a certain way? This constant questioning nags in the player’s mind as they race to figure out what is truly real and what is simply for aesthetic horror value. How

Silent Hill aids (and confuses) the player is with its camp 90s horror dialogue.

Silent Hill perfectly uses the principles of thin and thick description with its character writing. Thin description is simply the non-biased visual description of an object, environment or person. Clifford Geertz’s thick description is a description that doesn’t purely encompass [a] physical behavior but its context within an environment. Details and the “true nature” of a character slowly reveal themselves throughout the course of the game[s] as these members of comunitas descend further into the town. When James Sunderland, protagonist of

Silent Hill 2, meets Eddie Dombrowski he’s vomiting over the toilet after seeing a corpse. A thin description would be: An overweight man with blonde hair is wearing a backwards blue baseball hat and a striped blue shirt. But immediately from his dialogue and mannerisms, "I didn't do it... I swear I didn't kill anybody." There is a small layer of thick description given to the player. Throughout Eddie’s story arc, he frequently brings up his weight and how others would treat him because of it. He slowly becomes more unhinged and unfeeling towards his peers, “That guy... he had it coming! I didn't do anything! He just came after me! Besides, he was making fun of me with his eyes, like that other one!" As Eddie becomes more friendly with James, he quickly becomes paranoid that James is “like all the rest of them.” Eddie arc’s ends when he succumbs to own feelings of inadequacy and lashes out at James. “Maybe I am nothing but a fat disgusting piece of shit! But you know what? It doesn't matter if you're smart, dumb, ugly, pretty... It's all the same once you're dead!” As Eddie attacks James, he shoots in self-defense, killing Eddie. But even after death, James shows remorse for the psychotic young man, "Eddie? Eddie! I... I killed a... a human being... a human being..."

An interpretation of Eddie’s character is that

he is the monster manifested by the Otherworld. While other creatures such as the Abstract Daddy and Closer are based on the vile acts of off-screen characters, the places Eddie shows up often only feature him -- the sole threat. Eddie could be a creature in the vein of Abstract Daddy and the Closer -- but instead of manifesting as sexual violence, he is an aspect of physical violence. Like the Otherworld and its influences on the town’s monsters, characters like Eddie juxtapose the cast of human characters by posing the question if those safe spaces were really all that safe to begin with.

Silent Hill isn’t good at manufacturing its sense of psychosis purely on its art direction -- but its ability to juxtapose it against small specs of humanity. When juggling the violent sound direction, surreal visuals and stressful gameplay, it becomes difficult for a player to distinguish what truly is real and what impact they truly have. The tools it gives players to defend themselves actively make the player fear themselves and their inability to make the right choice. And even if they can make every correct decision, things may still fall outside of their control and they’ll be left to pick up the pieces.

Thanks for reading. Return to the library by clicking here