All religions have a basis in spiritual mysticism. Their beliefs would manifest into art -- stories were visualized with new mediums and would aggrandize the work beyond literature. While the Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism and Islam) all stem from the titular Hebrew patriarch, their respective writings all portray themselves much differently from one another. The imagery of religion is also based on the secular life around it.

Italian painters were commissioned to paint religious imagery as the line between secular and religious life was often blurred. Works created during the renaissance were inspired by a myriad of different stylistic influences -- like the Christian imagery of surviving Byzantine art. With the introduction of new materials, like Flemish oil paints, Italian artists were able to achieve a level of detailaccuracy that was previously impossible.

The main idea of the ‘New Renaissance’ is that old ideas would be reinterpreted, recontextualized and recreated with a new spin put on it. Humanism is the philosophical movement associated with personal betterment and scientific advancement. Italian artists were as concerned with advancing science as they were about advancing cultural iconography. The best example of this can be seen with the Italian cherubim. Previously represented in the bible as a four winged, four headed (ox, lion, eagle, human) angel who served as God’s protectors, the cherbum took on a new representation. The puttoputti is a small, chubby boy with wings whose design is based off of the Roman deity Cupid. Likely because of the humanist movement and the advancements made regarding the human body, artists (and their patrons) wanted naturalistic representations of the human body and subsequently angels. Angels such as Gabriel or the Virtues were illustrated as their appearance made it easy to imprint upon and relate to.

Demons in Italian art were almost the opposite. While still distinctly humanoid, they featured more animalistic features than angels (often just avian wings). Illustrated to be ugly, violent and ‘feral,’ demons juxtaposed angels, heaven and the virtuous lifestyle the religious world wanted to promote. These illustrations would act as a deterrent to a sinful lifestyle -- an omen of hell and the torture if they did not live their lives as good, worshipping Christians. Their purpose in storytelling is almost exclusively to be one-sided faces of evil and sin or to be fodder, crushed by the popular and beautiful angels.

Circa 1470-5

The workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio

Italian, about 1435 - 1488

Egg tempera on poplar wood

Tobias and the Angeli is a Judiac story about the titular Tobias going on a journey to collect a debt for his father. On this journey, the young boy is accompanied by one of the seven archangels Raphael. The Book of Tobit, the fiction from which his story derives, is the first piece of literature to name Raphael.The angel guides Tobias though his journey as he was sent to do so by God.

In late 15th century Florence, it was common among confraternities to pledge devotion to the archangel, Saint Raphael. It is likely that this piece was commissioned by one of Florence’s rich mercantile class due to the similarities between them as Tobit, Tobias’ merchant father.

However, the painting is notable not for its subject matter but the means of its creation. The painting is attributed to Andrea del Verrocchio and an unknown assistant who is commonly believed to be Leonardo da Vinci. This theory is supported by the varied qualities of the painting as well as the knowledge that Leonardo da Vinci was trained in Verrocchio’s workshop.

The most recognizable details of Verrocchio’s work are his representation of the eyes and the halo. The eyes are recognizable due to the heavy emphasis placed on the colorization of the eyelids and eyebags. Verrocchio’s figures have well defined eyes that often denote the underlying anatomy that lays beneath it. Additionally, Verrocchio’s design of the halo differs from other representations as it is a reflective, metal disk that floats above the angel’s head. In Tobias and the Angel, the sky and environment around Raphael can be seen reflected by his halo.

However, due to the inconsistency in the painting’s quality, scholars have hypothesized the painting to be aided by one of Verrocchio’s assistants -- namely Leonardo da Vinci. One of the inconsistencies mentioned is the differing quality of rendered fabric. The blue cloth worn by Raphael, Tobias’ pants and his top lack the weight and 3d dimensionalities that other garments of clothing possess. A key component of these garments are their distinct lack of highlights -- this absence is what gives them their overall dull and unfinished look. These clash against the figure’s other clothing, such as Raphael and Tobias’ extremely detailed sleeves.

Circa 1537

Domenico Beccafumi

Italian, 1486-1551

Oil on poplar wood

Saint Francis of Assisi Receiving the Stigmata is a wooden predella painted by Domenico Beccafumi for the Oratory of the Compagnia di San Bernardino. In 1273, the confraternity was dedicated to both Mother Mary and Saint Francis of Assisi. Why this piece is commissioned is likely because it parallels Mother Mary’s annunciation -- a story also present in the oratory.

This painting of Saint Francis receiving the stigmata is much different from previous iterations -- notably Giotto’s representation. While Giotto’s representation shows all figures of equal size, Beccafumi does not. Beccafumi emphasizes that the story is about Saint Francis by making him the largest figure in the painting. The lines used to illustrate the receival of the stigmata (paint knife on oil) guide the viewer’s eyes to the small figure in the sky. Due to damage done by the painting, it is not entirely known if this seraph is or isn’t Christ.

Brother Leo is slightly off to the right of the seraph, remaining in the final third, disconnected from the rest of the composition. He blends in with the background, his robes painted with similar colors to that of that naturalist landscape. Additionally, he is illustrated to be in shadowhalf-lit, as opposed to Saint Francis whose entire body is practically lit by the seraph.

The small representation of the seraph may also be a representation of the sun. The origin of the name Seraph comes from the Hebrew verb, lisrof (לשרוף), which means “to burn.” Seraphs are angels of the highest order and defend God’s throne by burning. This coincides with Saint Francis’ rapidly declining health after receiving the stigmata -- he is cited as being “almost totally blind,” which would align with the theory of him gazing upon the sunseraph.

Circa 1502

Lucas Signorelli

Italian, 1441-1523

Fresco mural painting

Signorelli’s vivid and brutal imagery can be attributed in part to Girolamo Savonarola. Savonarola, a Dominican friar, was renowned for his denouncement of immoral ideas. He held much influence in the city of Florence and encouraged its citizens to repent for their sins. As the new century grew closer, his sermons were able to instill a grand fear of hell and the consequences of not repenting.

The fresco lacks an in-depth biblical story -- but it doesn’t need one. Signorelli creates an image that parallels Savonarola’s teachings and gives a real depiction of consequence. By not repenting, Signorelli shows the brutality of damnation. He depicts the sinners as lean, muscular and in visceral yet very real pain. Signorelli uses hatching in order to texture the human body. Hatching is an artistic technique used to grant texture by applying repeated lines in a single uniform direction. Skinny figures and the texture applied with hatching allow the brutality to not only be observed, but felt. Standing away from the chaos, the angels support the narrative by sheathing their swords, unable to help the sinners.

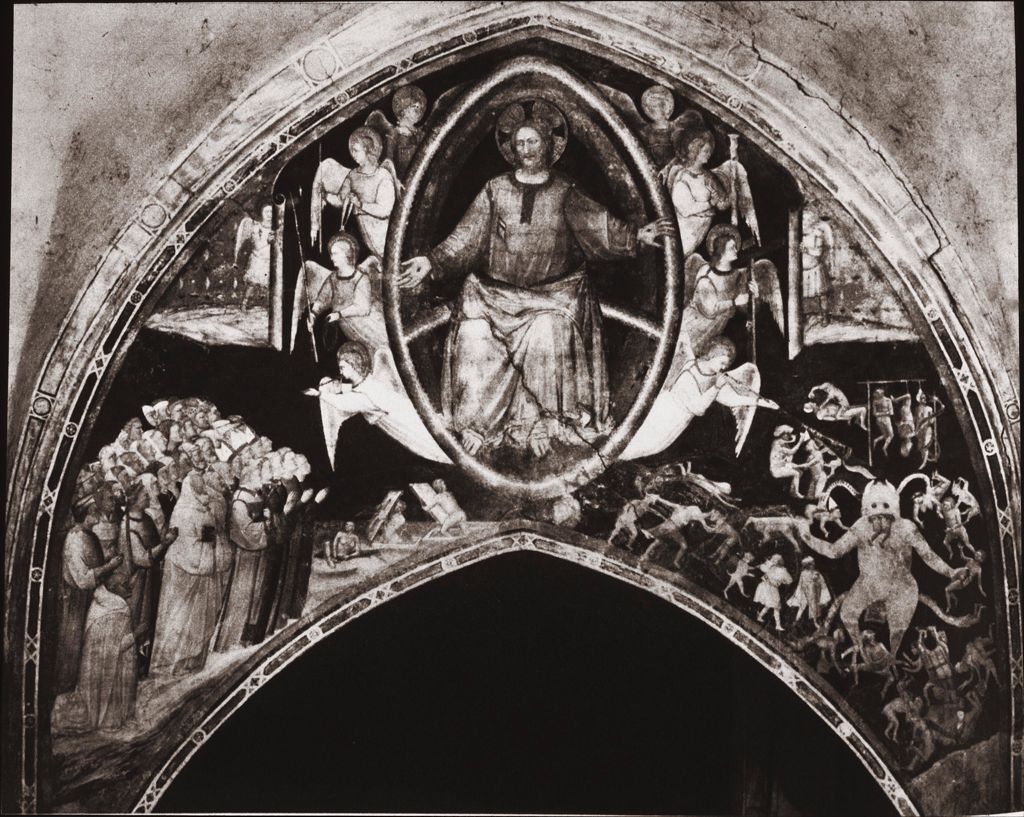

1349

Giusto de Menabuoi

Italian, 1320–1391

Fresco mural painting

The Last Judgement by Giusto de Menabuoi visually possesses many of the tenants commonly associated with the biblical scene. Two sideways registers broken by Christ represent the chosen and the damned. These sides are visualized by the symbolism of Christ’s hands -- his right arm raising the chosen to heaven and his left arm lowering the damned into hell. What Christ neglects are the fate of the damned as they’re torn apart and violently murdered by a band of demons.