* Art Resources

Anatomy for Sculptors (Google Drive)Anatomy for Sculptors is one of the most comprehensive and detailed anatomy books for artists. It explores complex human anatomy while breaking everything down into primitive shapes for easy understanding.

Rating:

Drawing Books (Website)Anna's Archive (Website)A resource of other anatomy books if Anatomy for Sculptors is not to your liking.

Additionally, Anna's Archive is an archival website that hosts many great artbooks, such as Henry Dreyfuss' Symbol Sourcebook, that was famously used by Jean-Michel Basquiat in much of his artwork.

Rating: Varies

Dither Me This (Web app)Dither It (Web app)Dithermark (Web app)Various webapps for dithering images and artwork, each with differing levels of complexity/depth.

Rating:

The Met Collection (Website)The Metropolitan Museum of Art colloquially referred to as the Met, is an encyclopedic art museum in New York City. It is the fourth largest museum in the world and has over 490,000 objects of art in its collection, which are all accessible via their online database.

Rating:

Digital Brushes (Tumblr)11 Free Brush Packs (Artstation)Various brush packs I've collected over time. This entry in particular will subject to change as I'll add more as I collect brushes endlessly.

Rating: Varies

Material Maker (App)Screenstone Generator (Website)Material Maker is a fantastic application that uses geometry nodes similar to Blender for making textures.

Screentone Generator is a good web app for generating screentones fast and easy online.

Rating:

Reference Angle (Website)X6UD (website)Reference Angle and X6UD are two resources great for those cheeky drawing angles that you need an eerily specific reference for. Reference Angle is used for people and X6UD is for animals.

Rating:

Symbolikon (Website)Symbolikon is a large online database of cultural symbols from across the world. A great resource all around, but I would mention that their sources aren't overly mentioned so take everything with a grain of salt.

Rating:

GlazeShare (Website)Glazeshare is an online community where potters can share their pottery and glaze combinations for all to see. Incredibly useful and inspiring for potters.

Rating:

The Nightshade Project (Website)Nightshade and Glaze are respectfully the offensive and defensive for artists to combat generative AI models from stealing their work. Worth checking out for any artist with stake in the current AI landscape.

Rating: Indeterminate

Spomenik Database (Website)An exploration of Yugoslavia's historic and enigmatic endeavor into abstract anti-fascist WWII monument building between 1960 & 1990.

Rating:

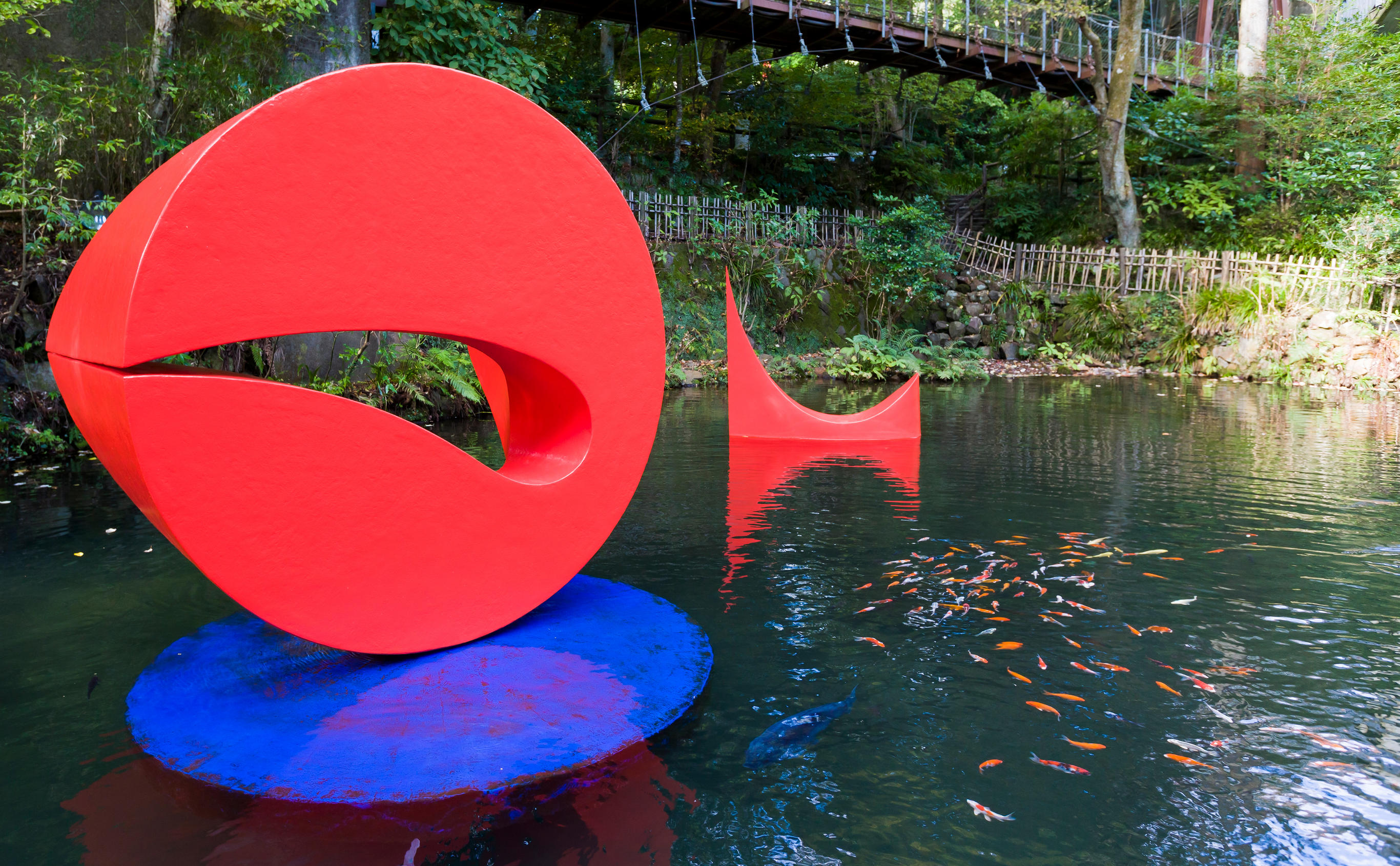

Hakone Open Air Museum (Website)The Hakone Open Air Museum is one of my personal favorite museums of all time, only rivalled by the Met and the MoMA (SF, NYC). Although its all the way in Hakone, Japan, I would recmomend everyone try and go to it.

Rating:

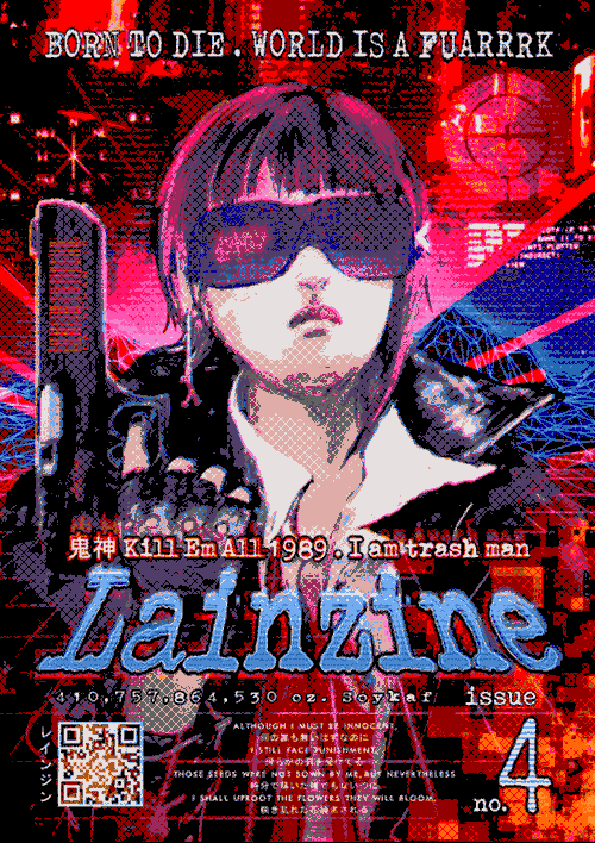

Photomosh (Web app)Photomosh is a great online tool for manipulating images and mp4s with strange effects. Though the free version has a lot of tools, the real meat is stuck behind a $24-49 dollar paywall.

Rating:

You've reached the end of Art Resources (for now...). To return to the top, click here.